Education in Bredjing Refugee Camp: Teacher/Student Abdel Razik Mohamed

The following special report from our on-the-ground partner Anne Goddard of CORD tells the story of Darfurian refugee Abdel Razik Mohamed, pre-school teacher and English student in Bredjing Camp, Chad. By sharing his experience, we hope to convey the refugees' yearning for education. Please donate to support Abdel Razik, his students, and fellow teachers.

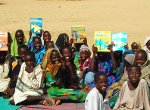

The final task of my predecessor working in Bredjing Camp was unenviable. She had to arrange a pre-school programme for some visiting dignitaries from UNICEF – during the summer vacation. The solution, however, was a stroke of genius. She left the whole responsibility to Abdel Razik Mohamed and by the time we arrived there was a group of several hundred children singing, playing and demonstrating a perfectly organised and perfectly disciplined pre-school programme. Even more of an achievement because Abdel Razik was running this programme without the help of any other colleague.

The final task of my predecessor working in Bredjing Camp was unenviable. She had to arrange a pre-school programme for some visiting dignitaries from UNICEF – during the summer vacation. The solution, however, was a stroke of genius. She left the whole responsibility to Abdel Razik Mohamed and by the time we arrived there was a group of several hundred children singing, playing and demonstrating a perfectly organised and perfectly disciplined pre-school programme. Even more of an achievement because Abdel Razik was running this programme without the help of any other colleague.

That was my first meeting with this gifted and charismatic man. Aged 28, he originally comes from the village of Touraju, just outside the larger town of Mastaré in the west of the Darfur region. Before the people left the village on the 2nd February 2004, it was a thriving community centred on trade, with 381 houses and just under 2,000 inhabitants. These days, just three buildings remain standing, the rest burned by the Janjaweed.

At that time, Abdel Razik was just completing his secondary education in El Geneina, the largest town in Western Darfur and hoped to take further studies so that he could work in the public schools as a pre-school teacher. Unfortunately, he was never able to complete his studies and was just four months away from taking his final exams that would have granted him a place at university, when he had to flee over the border into Chad.

These days he is CORD's head teacher for the pre-school in Ousman School, Bredjing Camp. Six days a week, he works from around 7.00am to 9.45am with 300 children aged between 3 and 6 years, helped by four colleagues. With my white skin, I tend to cause a terrible distraction to the pre-school students when I visit, so I look from afar at some very lucky young children listening to stories, singing and playing. However, I need not worry about approaching Abdel Razik’s group because he can win back their attention in an instant – they clearly love this man. What is more than obvious is that he clearly has a big heart for each and every one of them.

Yet Abdel Razik is not only a teacher, but also a student and I went to visit him in his home which he shares with his wife, Tayiba and their 3 year old daughter, Nidaal. In the compound, which measures approximately 5m x 5m (16' x 16') he has built two small shelters, one out of bricks which he has made from mud, baked in the sun and the other from grass stalks. Tayiba has the place swept scrupulously clean and there were some red lentils drying in the hot sun. There was little furnishing except for two old metal chairs and a small bed. In spite of their humble situation, Tayiba presented us with cool water to drink and dates and fried biscuits to eat.

Yet Abdel Razik is not only a teacher, but also a student and I went to visit him in his home which he shares with his wife, Tayiba and their 3 year old daughter, Nidaal. In the compound, which measures approximately 5m x 5m (16' x 16') he has built two small shelters, one out of bricks which he has made from mud, baked in the sun and the other from grass stalks. Tayiba has the place swept scrupulously clean and there were some red lentils drying in the hot sun. There was little furnishing except for two old metal chairs and a small bed. In spite of their humble situation, Tayiba presented us with cool water to drink and dates and fried biscuits to eat.

Six mornings a week, before the primary school lessons start, Ousman School is known as Unity School and is a centre for English language learning. Abdel Razik is one of the 400 students and along with each learner he contributes a small sum per month in cash or kind to a central organising committee, out of which the teachers are paid. The six classes are well-organised into levels of ability and the students are of all ages, girls making up 40% of the learners. They start their class at approximately 6am, finishing after 45 minutes as the primary students arrive. In the early evening before sunset and after the heat of the day has passed, a further 60 advanced learners arrive to study together.

They are using the Oxford grammar books that the Sudanese have either brought with them, or have purloined along the way. These present perfectly accurate English grammar, but are over fifty years old and somewhat outdated. They also have some SPINE English learning books that are used in the Sudanese national curriculum. However, there are many students and few books. That is why CORD and Book Wish Foundation are trying to provide books from the Headway English language learning course, which is preferred by the Sudanese.

After Abdel Razik has finished his English lesson, he goes to teach the pre-school children. However, at the other end of Bredjing Camp, there is another English language centre at Abubakar Assadik School that meets in the late afternoon where around 200 students of all ages gather to learn. They are using the same textbooks, pay the same fee and are controlled by the same committee.

After twenty minutes we were joined by two senior men who work hard on the school committee*. Although there are many difficulties living as a refugee in a country that is in itself highly unstable, together with Abdel Razik they agreed that the best thing about being in Bredjing Camp is the education. Formal education is free and they know that if they and the coming generation are to succeed, they must be educated. This is not only for the men and boys, but for the women and girls too and their words are given weight by our statistics of high attendance levels in schools, high pass rates in exams and an almost equal percentage of male and female students.

Although there are radios in the camp, the three men were keen to ask me if I had any current news of the peace process in Darfur. I was not able to give them the information they are longing for because there has been no lasting peace agreement and for the foreseeable future it will not be safe for them to return to their village and rebuild their community. Abdel Razik wants nothing more than to provide for his family and to go to college to complete his studies. For me, it remains both a challenge and a privilege to try and find the resources to help him and others like him achieve their ambition.

Anne Goddard

Programme Manager for Education in Bredjing & Treguine Camps

Hadjer Hadid, Chad

March 2008

*Each school is run by a committee of ten people. They make sure that teachers are present and in the classrooms, hire and fire, ensure fair distribution of materials and build the grass classrooms. They also go into the communities and make sure that the children are in school and encourage those who are not attending. They meet each week to discuss the work of the school and are supposed to have a couple of members present on the premises whenever the school is open. They are quite a powerful body and we do nothing that involves radical change without going through them. Of course, this sounds very advanced and some of the committees work better than others, but is generally true that the better the committee, the better the school.