Essay Contest Winners

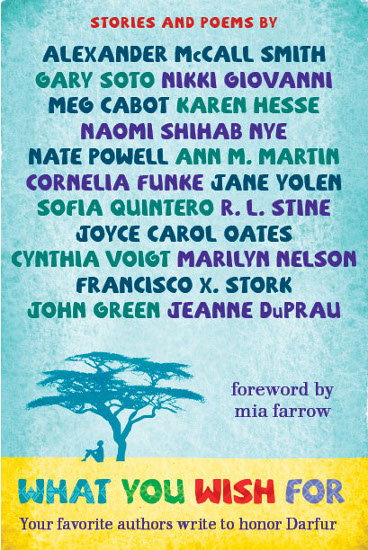

Book Wish Foundation is thrilled to announce the winners of our essay contest for aspiring writers. We asked readers of our new book, What You Wish For, to write how the wishes in six of the book's short stories are related to the refugee situation in eastern Chad, where nearly 285,000 Darfuris live in 12 refugee camps, afraid or unable to return to Sudan after the genocide that destroyed many of their families and homes. The stories were contributed for free by their authors so we could use the book's proceeds to develop libraries in the refugee camps. Many excellent essays were submitted, but we could choose only one winner per story to receive a rare and valuable manuscript critique from the story's author or the author's literary agent. After preliminary judging by Book Wish Foundation staff and final selection by the authors and agents, we are pleased to reveal the six winners, listed by story:

- "The Protectionist," by Meg Cabot. Sue Firth Welfringer has won the manuscript critique by Laura Langlie, literary agent for Meg Cabot.

- "Pearl's Fateful Wish," by Jeanne DuPrau. Cathy C. Hall has won the manuscript critique by Nancy Gallt, literary agent for Jeanne DuPrau.

- "Nell," by Karen Hesse. Courtney Sender has won the manuscript critique by Brenda Bowen, literary agent and editor of Karen Hesse's Newbery Medal winner Out of the Dust.

- "The Lost Art of Letter Writing," by Ann M. Martin. Mary Jo Burke has won the manuscript critique by Ann M. Martin, winner of the Newbery Honor for A Corner of the Universe.

- "The Rules for Wishing," by Francisco X. Stork. Julianne Dillard has won the manuscript critique by Francisco X. Stork, winner of the Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award for The Last Summer of the Death Warriors.

- "The Stepsister," by Cynthia Voigt. Yvette Burnham Couser has won the manuscript critique by Cynthia Voigt, winner of the Newbery Medal for Dicey's Song and the Newbery Honor for A Solitary Blue.

Congratulations! The authors and literary agents are looking forward to reading your young adult or middle grade manuscripts (check your email for details).

If you did not win, please note that essays were judged on the four criteria of style, creativity, understanding of the story, and understanding of the refugees. Some essays were very strong in one or two of these areas, but were not as competitive overall. In the coming weeks, we will share excerpts from many of the essays and discuss some of the most interesting approaches to the essay question. Thank you to everyone who entered! We are tremendously grateful for the time you spent with What You Wish For thinking about the Darfuris the book aims to help.

Here are the six winning essays, in their entirety (spoilers about the stories ahead):

Sue Firth Welfringer's winning essay about Meg Cabot's "The Protectionist"

Picture this: one child, Dave, looks out his bedroom window, over his backyard, and into the night. His universe sits above a professionally designed, well-manicured golf course. He reaches towards the milky darkness, picks a star among the few, and makes a wish.

Now, imagine another place and another child, Beina. She steps outside her family’s windowless hut onto the mud-packed entrance and looks up to the night. Her black sky universe covers a harsh and unfriendly, barren desert. She reaches for the sky, chooses a star among the millions, and makes a wish.

Dave wishes the daily violence against him will end. He wishes for a sense of security.

So does Beina.

She wishes to gain greater control of her destiny. She wants her dignity back.

So does he.

Dave wants his bike back, stolen by a bully, tormentor. Beina wants her village back, destroyed by the Janjaweed militia, tormentors.

Both children need protection. They both would love a friend.

So they make their wishes.

But the stars, holding on to their power, aren’t granting wishes today. They have other pressing issues on their mind. They assemble over the golf courses, the oceans, the deserts and mountains, fully engrossed in their own well-being, too busy to be bothered with the simple wishes and idle dreams of children.

The boy has a teacher, his sister. She tells him wishes don’t just happen. Wishes need help. If he wants to hold onto his dignity and freedom, he has to take action. If he wants a friend, he’ll have to work at it. If he wants his bike back, wishing isn’t enough. And, like the good AP scholar he is, Dave takes her words to heart and learns. Things get better.

The girl has a small library. It’s tucked inside in the child-friendly center of the crowded refugee camp. She’s found true friends in the books she reads, filled with truth and hope, struggle and promise. Her imagination is fueled. And, like the determined visionary she is, Beina takes these stories to heart and learns. Things get better.

And, while the stars hold their place in the heavens, education holds its place on earth. “Education is the one thing that we can give that can never be taken away.” A powerful thought. Doesn’t every child in the world deserve an education? After all, with education comes possibility. And what is a wish, if not a possibility?

Meg Cabot's literary agent, Laura Langlie, commented, "The winning essayist gave me some hope that there are like-minded people in this world willing to take action to improve the lives of others. What's possible can be made probable, and wishes can come true--with action." Truly, this is a message that all of our supporters have taken to heart.

Cathy C. Hall's winning essay about Jeanne DuPrau's "Pearl's Fateful Wish"

It’s hard to imagine the need for solitude when I sit here in my home office, with only a small, humming space heater keeping me company. My husband is off at his work, my grown kids are away, in school or at jobs, and so I’m often alone in my house, to write, to think, to daydream as I gaze outside my windows. When I lean over my desk and look out those windows, I see a typical suburban American neighborhood; houses across from me, houses beside me, but none so close that I cannot have privacy any time I like. Having time to sit alone, to be alone with my thoughts is not an issue for me. Perhaps that’s why Pearl’s fateful wish, the wish to be left alone, jarred me so.

Such a simple wish, to be left alone! But even such a simple desire is impossible when living in a Darfuri refugee camp where row upon row of tents bunch together looking like a sea of hanging sheets upon a never-ending clothesline. And in each tent a family, all more or less like your own, trying to survive.

Here is a mother, holding her crying child. There is a young boy shouting, and over there is another boy, shoving, pushing, playing with a group of loud, rambunctious boys. A little girl lies on a blanket inside her tent, too weak to lift her head, while her sister recites a lesson. Another girl, who may have been married by now, had she grown up in her village, sits on the hard ground, longing in her eyes.

So many lives, cramped together, day after day, one year following another, making do with the challenging conditions forced upon them. Perhaps there are other, more urgent physical needs to be met than a small place of one’s own.

But then I look out of my window at all that space and I sink back in my chair and let my thoughts wander to stories in all the quiet places in my mind, and then I know. I know that a place of one’s own is as much an emotional need as a physical need.

For Pearl, surrounded by a vast sea of sameness, the need to be left alone pushed her from the comfort of complacency to the jolt of rebellion. And it is not coincidence that the apartment where Pearl found her respite belonged to a writer.

Writers understand the left-alone place, the quiet space where one can gather thoughts and dreams and wishes, too. Worlds apart, a suburban writer and a Darfuri refugee, but a common need ties them together. Still, it took Pearl’s fateful wish for me to recognize how much.

This winning essay shows a very personal understanding of the issues of space and place that Jeanne DuPrau's story urges us to think about in the context of the refugees. Most of us will never experience firsthand the conditions of a refugee camp, but "Pearl's Fateful Wish" can help us imagine one aspect of them in terms that are relatable to our own lives.

Courtney Sender's winning essay about Karen Hesse's "Nell"

Karen Hesse’s “Nell” is about life, death, and sacrifice—but, moreover, it is about the power of storytelling to change a life. In Darfur, the possibility of death haunts refugees’ childhoods, as it does the twelve-year-old soul at the center of “Nell,” who constantly inhabits other twelve-year-old bodies on the verge of death. Yet in Darfur, as in “Nell,” storytelling serves several functions that can save a life: it alerts those who can help that something might be done; it provides a refuge of the mind for those in bodily exile; and it offers the possibility of new and different narratives for the future.

“Nell” opens with the lines, “I am dying. I have been dying for a hundred years. I fear I will always be dying.” This speaker is able to “jump” into the bodies of dying children, bringing them to the brink of death without dying herself. In the context of Darfur, this seems like a wish in itself: that some other, practiced soul would take the place of the innocent at the time of their deaths. Yet the speaker in “Nell” no longer wants such a life. “Always is a long time,” she tells us, denoting that it is not a life to exist always on the verge of death. This is a lesson the children of Darfur have already learned.

Now inhabiting the body of a girl named Nell, the jumping soul seeks guidance in the story of the Little Match Girl. Miraculously, she sees a child outside her window who embodies the match girl herself. Reading her book gives Nell insight into the girl’s fear, coldness, and hunger. By understanding the story, Nell not only understands the girl but empathizes with her. “I can’t let her go on that way,” Nell thinks. The book enables Nell to achieve a degree of compassion that drives her final, selfless act: she wills herself into the body of the little match girl, allowing the match girl to live while the jumping soul ends her cycle of rebirth at last.

And here is the most powerful emblem of Darfur: under conditions of hunger and poverty, life and death, words and stories may seem impotent. Yet they allow Nell to access the humanity within the shell of the starving girl’s body, and they enable her to empathize and act. Similarly, the words and stories of and about Sudanese refugees allow the rest of the world to see past the horrifying photographs of scarred men and emaciated children. Stories go behind this horror, showing us people with wishes, dreams, and histories. Furthermore, stories—in the form of books in libraries—would enable Sudanese refugees to perform their own body-jumping: to imagine themselves in some different time or place, and to derive comfort, strength, and hope from that imaginative jump. Karen Hesse’s “Nell” shows the power of storytelling to save, to fight against death both by encouraging human fellowship, and by offering mental escape and renewal to those who need it most.

Literary agent Brenda Bowen praised Courtney's essay for "the clarity of the prose, the lucidity of the argument, and the deep understanding of Karen's story." Those who have read "Nell," Karen Hesse's stunning story, will appreciate that it asks for a very thoughtful reader and is ripe for the kind of analysis shown in this essay.

Mary Jo Burke's winning essay about Ann M. Martin's "The Lost Art of Letter Writing"

In The Lost Art of Letter Writing, Ann M. Martin has her characters, forced by a school project, become pen pals. At first, they assume stereotypes of each other. As the letters continue, all melts away and the girls reveal their true lives to each other. Children in difficult situations grow up quickly. In America, unemployment, extended families living together, and poverty leave children alone and afraid for the future. In Darfur, children have hopes and dreams, but survival supersedes all.

Children dream about the future. They look beyond the lives they lead and imagine the next step. Never dwelling on the past, to them, all is possible. Wishes and goals are the topics of everyday conversation. They are eternal optimists despite their circumstances. They imagine a way out and a road to achievement. Darfur’s children, despite adversity, feel the same way. In Mia Farrow’s forward to the book, Mohammed overcomes the death of his parents, teaches himself English, and yearns for more. He knows he is worthy and capable.

All he needs is a chance.

Jen and Allie wrote letters of comfort and consolation. They have much in common and try to help each other through difficult times. They don’t ask much, just listen and understand. They need a sounding board and reassurance that this too shall pass. The girls in the story cling to each other as their lives change around them. It is a friendship forged in adversity and being built to last.

My great uncle was a priest who lived in Rome and Kenya. I wrote to him and cherish his typed letters. He explained his handwriting was too big and he could get more on the paper with a typewriter. He reflected on his work and the people he met. After his death, I heard of the many lives he touched and those who sought his counsel. Mostly through personal letters and other correspondence, he was a wonderful listener and a wise soul.

Darfur’s needs are too great to list, but libraries are a first step towards normalcy. Books are the beginning of the learning process. To read is to be opened up to knowledge and ideas. It’s the way to form opinions and understand the world. It also expands the imagination and unlocks creativity in every person. Writing flows from reading. Libraries nourish because the atmosphere is one where life slows and lingering is required. The urge to start at one end and read through to the next is palatable. I write because I’ve read books all my life. They transport through time and space. They’ve become a part of me.

Reading and writing go together. When children are exposed to both, the art of communication can lift their burdens and allow them to reach out to others. Darfur is a region scorched by battles and filled with despair. Libraries are a positive step and a wish fulfilled for the children and their future.

Author Ann M. Martin especially liked Mary Jo Burke's "thoughts on the children's desire to learn and what an education might bring to their future." Starting with its title, this essay shows that the rich emotional characterization of the pen pals in Martin's "The Lost Art of Letter Writing" can help us relate to the wishes of the refugees for their uncertain future.

Julianne Dillard's winning essay about Francisco X. Stork's "The Rules for Wishing"

The way Francisco X. Stork’s “The Rules for Wishing” unfolds in changing voices speaks to the nature of wishes and captures what it means to be able to wish even against the backdrop of darkness.

Mama’s letter at the start is removed—and in the distance created, the feeling of her desperation is muted. It reminds me of how we see news reports on tragedies like those that the children of Darfur suffer. They draw interest, but what can a person do? I’ve been like Pablo, who places the letter aside, not discarding it, but hiding it away because it is too painful to bear.

In part two, Sherry B. offers another way to approach the pain. In a setting where “everyone has problems,” Sherry B. doesn’t hide. Through her, we see openness and compassion to the other damaged but resilient guests of the home.

Still, we are outside, in the third person, and can glimpse Pablo’s need, but not really understand it. As Pablo explains the dream in his own words in part three, pieces fall into place. In describing the loss he hides from during the day, there is a chance to see within the tight cocoon of silence he’s created to weather it. We, no more than Sherry B., can precisely know Pablo’s pain, but her actions demonstrate how giving it voice and acknowledging it without turning away are meaningful.

Her actions are meaningful in that they spare Pablo. That he put the letter in a book like The Count of Monte Cristo — the tale of a man wronged and driven to desperate acts by his bitterness is telling. At that point, Pablo has the potential to live a life tainted with the darkness that fills the space of all that was torn away. It is Sherry B.’s recognition and encouragement of his wish that help Pablo evade choosing a path of revenge and bitterness himself.

In Sherry B’s voice, we learn of her effort to celebrate Pablo’s life and the makeshift candle/matchsticks, perhaps symbolizing unwillingness to give in to lack or to expectation. In wishing on a matchstick, Pablo goes from one who didn’t know he could make a wish, to one who believes. He tries. He dares to hope and even to share it.

I held my breath, wishing for Pablo to regain somehow what was lost. Reading such a moving story in the context of a book honoring Darfur, I see the futility of hiding from what seems to painful to bear. At the same time, “The Rules for Wishing” captures the value and necessity of wishes for the children of Darfur. Few will know truly what they have lost and suffered. But I can take what I know of the power of hope to help facilitate wishes that will make the difference between despair and hope. Through contributing to the libraries and opportunities that encourage the resilience and empowerment of Darfur’s children, I can “make the same wish.” I can be Sherry B.

Author Francisco X. Stork said that, “In her essay 'On Wishing to be like Sherry B,' Julianne Dillard elegantly and powerfully captures the connection between our natural instinct to wish and hope and how this instinct not only survives but must be preserved in the presence of the harshest of realities.” If everyone who reads Stork's story takes away this message, then we can certainly be more optimistic about the future of the Darfuri refugees and others who need our help to nurture their wishes.

Yvette Burnham Couser's winning essay about Cynthia Voigt's "The Stepsister"

“The Stepsister” by Cynthia Voigt is a bittersweet Cinderella story exploring the horror that results when wishes are granted. This account calls for justice, and with a cruel hand, justice is meted out.

After the Stepfather remarries, he caters to his new wife and her daughters, Yetiffe and Lysette; while his biological daughter, a quiet, obedient girl who is never named, works as their maid. The wife’s status results in an invitation to the ball and the social-climbing Stepfather is delighted. On the night of the first ball, the meek daughter appears incognito, captivating the Prince. Her early departure causes a ripple of wonder-filled gossip to spread through the crowd. There are subsequent balls, resulting finally in the mysterious lady losing a shoe and the King's charge to scour the kingdom for its owner who will wed the Prince.

Both Yetiffe and Lysette maim themselves in a desperate attempt to fulfill their wishes. Lysette has the foresight to cauterize her toes, but foolish Yetiffe bleeds to death from her mutilated heel. As Yetiffe lays dying, their stepsister reveals herself as the mysterious lady, and, full of sorrow she utters, “I didn't mean...” and “I never thought...” and finally, “I'm so sorry.” Her grief speaks to the powerful, darker side of wishes.

When justice is served, it is not a joyful occasion. In wishing to attend the ball, the stepsister released a series of events that rolled steadily toward judgment. She didn't just wish to attend the ball; she wished for freedom from oppression, for respect and human dignity, for the restoration of her place in her home. For this to happen there must be a reckoning.

In Darfur, justice will come. All involved wish for this, from the refugees living in desperation and fear, to the aid workers sharing the burden, to those abroad raising awareness and funding. As in “The Stepsister,” there will be a celebration, a new regime will be installed, but the history of genocide and scars from war will remain forever. Like the stepsister and Lysette, survivors must learn to live with the memory, for as George Santayana cautions, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Mercy balances the horror, for Lysette is invited to live in the palace, where her life shows reform. Perhaps it is under the watchful eye of the new government that she is allowed to live out her life, because the potential for corruption and evil will never truly be wiped from our lives. Nevertheless, “The Stepsister” remains a fairy tale, and, while a helpful means for teaching morality, these parallels can only stretch so far. The crisis in Eastern Chad is a reality. Voigt's rendering forces the reader to stop and think; the vivid horrors nag at us, as they should. Once we learn of the Darfuris’ plight, we must not shut the book and put it aside. We must go beyond the fairy tale and act.

Yvette Burnham Couser's approach to Cynthia Voigt's story was unique and grabbed our attention in the early judging. It reminds us of the horrible brutality that the Darfuris and other people sometimes endure in their quest for basic human freedoms, and how we must continue to remember those who were tragically lost during their struggles even when justice is eventually achieved.